The business of producing wholesome, quality food is a challenge. In addition to designing and manufacturing creative and tasty products, a laser focus on food safety is necessary for food processing companies to survive and thrive. Food safety is affected by the ingredient supply chain, ingredient and finished product transportation, facility design, machinery design, sanitation procedures and overall process control. Machinery that stores and processes raw ingredients or the finished product have a significant effect on the food processor’s ability to produce products that are not adulterated or spoiled.

Machinery procurement is an expensive and complicated process. Primary requirements always include the ability to produce the product at a desired rate with the desired quality and scrap level. In the past, many machine requirement documents did not include specifications for hygienic design, the ability to be cleaned or the ease of cleaning. These hygiene-related activities can significantly affect the total cost of owning the equipment, and forward-thinking companies include specifications for these items in their machine requirements.

According to Darin Zehr, general manager of Commercial Food Sanitation, “A great operating and food safe processor has hygienic design at its core.” This article identifies and proposes items that should be included in the monetization of hygienic design.

Impact of hygienic design

Hygienic design can quickly produce significant return on investment (ROI). The activities of accurately identifying, quantifying and tabulating the items that save costs, increase production and reduce risks are extremely important and determine which curve in Figure 1 represents reality. Accurate monetization enables better decision-making concerning materials, machine construction and purchased components. These items present problems in washdown environments and therefore significant opportunities for improvement.

Cleaning time & supplies

Cleaning equipment typically occurs on a regularly scheduled basis. Design characteristics that increase the amount of time required to clean equipment directly affects the amount of production time available and the direct labor costs of sanitation. Standard procedures for cleaning equipment with components not hygienically designed including assembly and disassembly of equipment, applying and removing temporary protective covers and hand-cleaning and a variety of other activities can be identified, quantified and monetized. This analysis is applicable for dry-clean areas as well as wet washdown areas. Electrical and motion products provide a significant opportunity for improvement in this area.

Choosing components that can be cleaned like the rest of the machine using water and cleaning agents can decrease cleaning time considerably. For example, cleaning a motor with water and cleaning detergents rather than hand-cleaning can save up to three to five minutes per motor per cleaning session. If a machine with three motors in production 260 days per year is cleaned daily and it takes three minutes of additional time to cover each motor during washdown and then clean each motor by hand, then 2,340 minutes or 39 hours of additional cleaning would be required each year just to hand-clean the motors. When all costs for cleaning time are considered, this small amount of time per motor quickly adds up to substantial monetization value.

In dry-clean areas, hygienic design may save even more time since water, one of the most effective cleaning tools, is not used.

In addition to saving cleaning time, better hygienic design may reduce the amount of cleaning agent required, allowing for the use of more cost-effective or safe chemicals, and provide water savings and wastewater reduction.

Lost production time from equipment failures

Equipment should be designed to be durable for the environment in which it is used. A survey of 30 food safety professionals participating in the Kollmorgen Advisory Council for Food & Beverage indicated they were aware of electrical components that failed at least monthly in washdown areas. A brewery maintenance manager coined the term “Shocking Monday” to refer to the four hours every Monday morning when the production lines did not run, or ran intermittently, because of electrical component failure after Sunday evening’s thorough cleaning regimen. Many processors have repair racks full of damaged, painted food-grade motors and other failed electrical components. Many of these components have failed because they were washed with water and detergents due to changes in cleaning procedures to improve sanitation or were washed when existing cleaning procedures were not followed correctly to protect the devices. As a leading Ready to Eat (RTE) food safety expert said, “Our motors are generally receptacles for water.” Washdown areas are rough on electrical equipment and failures have been accepted as the norm. Expensive, durable products have been almost regarded as consumable parts because of their failure rates. A new class of electrical products (see Figure 2) with IP69K ratings and engineered to withstand the washdown environment are now available. The increased cost of the products is easily justified when lost production caused by unplanned failures are accounted for properly.

Careful consideration should be given to the cost of lost production because of component failure. Those numbers should be included in the ROI calculation concerning using purpose-designed durable products in washdown areas.

Itemizing reduced risk

Hygienic design reduces the risk of costly food safety issues. Two financial events can be caused by ineffective sanitation. First, costly recleaning interventions are required when positive readings of selected pathogens occur after sanitation procedures. A second, more threatening event is a potentially devastating food recall. Electrical components that cannot be cleaned with water and cleaning agents like the rest of the machine and covers that are used to protect these components increase the risk of these events occurring. According to Pat Sigler of Keystone Foods, “Anything that has to be covered during sanitation (motors, electrical components, display screens, etc.) or is not accessible, does not get cleaned well.” The bottom line is that selecting machinery components that can be cleaned like the rest of the machine reduces food safety risk.

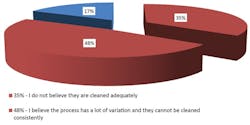

Components and the covers used to protect them often have rough surface finishes, metal-to-metal seams and connector hardware that create niches and dead spots that cannot be cleaned efficiently or effectively. These areas create risks during every sanitation cycle. Variations in cleaning procedures such as removing or adding covers and hand-cleaning electrical and motion control components increase the risk of ineffective sanitation. In a survey of 25 leading sanitation and food safety professionals, 83 percent indicated they did not believe that components covered during washdown activities and cleaned using alternate methods were consistently and adequately cleaned (see Figure 3).

While the reduction of risk is challenging to quantify, the cost of incurring food safety events could be enormous. Single recleaning events in RTE areas can cost as much as $15,000 while food recall events can cost millions. Increased spending on better hygienic design and hygienic components is easily offset by reasonable considerations of these risk reductions.

Conclusion

The cost of improved hygienic design for food production and primary food packaging machines is easily justified when the total life cycle costs of design defects or the use of lower-cost, less durable/cleanable components is considered and accurately calculated.

Bill Sutton is business development manager for Kollmorgen. He is an electrical engineer with 25 years of programming, design, marketing and sales experience. Sutton received a BSEE from General Motors Institute in 1986 and an MBA from Northern Illinois University in 1995. He is a Certified Fluid Power Specialist for pneumatics and hydraulics. Sutton also developed solutions including software and hardware to automate hazard analysis and critical control points activities. He has concentrated on food processing and packaging equipment for the last 10 years and was a member of the OpX committee that produced One Voice standards for Hygienic Design.